US Banks Continue To Resist True Open Banking

June 30, 2022

Open Banking and Strategy

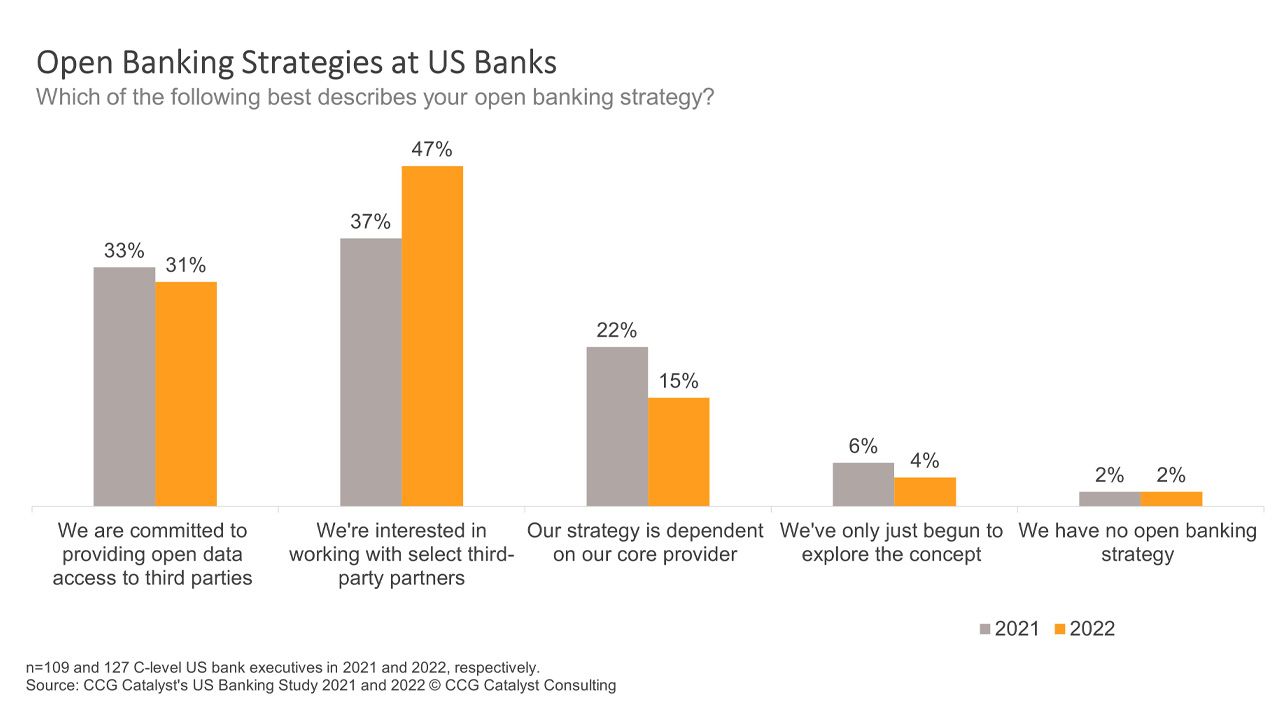

As the US creeps closer to formal open banking rules, many banking institutions in the country are still resisting the concept in its true form. In fact, according to CCG Catalyst’s 2022 US Banking Study, just about a third of C-level executive respondents from US banks said their organization was committed to providing open data access to third parties, aligning with the definition laid out in other jurisdictions by regulation like the Second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) in Europe. That’s about the same as in last year’s sample. Encouragingly, 47% said they were interested in working with select third-party partners, which is up from 37% in 2021, while those dependent on their core provider to define their open banking strategy dropped from 22% to 15%. However, while it’s certainly positive that banks are moving to own their strategies on the open banking front, this activity is somewhat muted by the fact that it’s missing the mark on the open data conversation, indicating that we are still a long way from widespread industry understanding of what open banking is and what it means to implement it.

To be fair, it seems that our country’s regulators are grappling with similar hurdles. In early May, word broke that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was struggling to draft an open banking directive because of privacy concerns, specifically around how to protect customer data and govern how it’s used by companies it is shared with. While arguably admirable, this also somewhat evades the point — the key tenet behind open banking is that customers are in control of their data, and they are able to share it freely as they wish. Of course, this must be done securely, but other jurisdictions have provided blueprints for that. In Europe, for example, third-party providers that want to participate in open banking are required to get licensed. They are also required to use your data as agreed to at the point of consent. It’s likely that, as it further explores and understands the possibilities, the CFPB will use similar levers to develop its own framework. To this end, the agency later in May announced the launch of the Office of Competition and Innovation, which is expected to dive into the particulars of these issues, but this will take time.

The bottom line is we’ve been talking about open banking the US for a long time but thus far have made very little progress in implementing anything that resembles the schemes achieved elsewhere. And it seems as though we still have quite a long way to go. It will take mental leaps on the part of many different actors, from banks to regulators, and eventually, to consumers (who will require outreach and education around open banking) in order for any of this to become a reality. In the meantime, we are left with a patchwork effort, as is borne out in the data, by which we are all using different definitions for a single concept. Importantly, getting to open banking in the true sense is critical not only for competition, but ironically, also for privacy and security reasons. Sharing data via standardized application programming interfaces (APIs) is far more secure than the screen-scrapping that’s happening today when consumers want to use third-party apps, which requires users to share their actual login credentials. Like most things, though, this all comes down to understanding and fear of the unknown. In the US, we’ve not yet got a good enough grasp on open banking to embrace the benefits. Over time, that will likely change, but it’s going to take a real willingness to learn and keep an open mind, on all our parts.